Training dynamics of target weighting

There are different ways to construct training targets for value networks in chess engines. Some ways are much better than others, but these methods can be impossible to discover if one does not also account for how they affect the scale of the network's output evaluations.

Datasets and target construction

Typical datasets for training value networks for chess engines contain many positions from self-play games, where moves are selected by searching a small, fixed number of nodes per move. These positions are labelled with both the eventual outcome of the game (which we shall call ) and the value estimated by the engine during self-play (which we shall call ). To compute a target prediction for a position, we typically linearly interpolate between these two values, passing through a logistic function to convert it to the range first. The interpolation is controlled by a weighting parameter as follows:

Note the use of 400 as the sigmoid scale factor here. This is done to permit centipawn-like values for to correspond to reasonable probabilities after passing through the logistic function. This scale is reversed in network inference, where the network's output is multiplied by 400 without being passed through a logistic function.

Evaluation scale drift

When networks are trained with different values, the scale of their output evaluations can drift significantly.

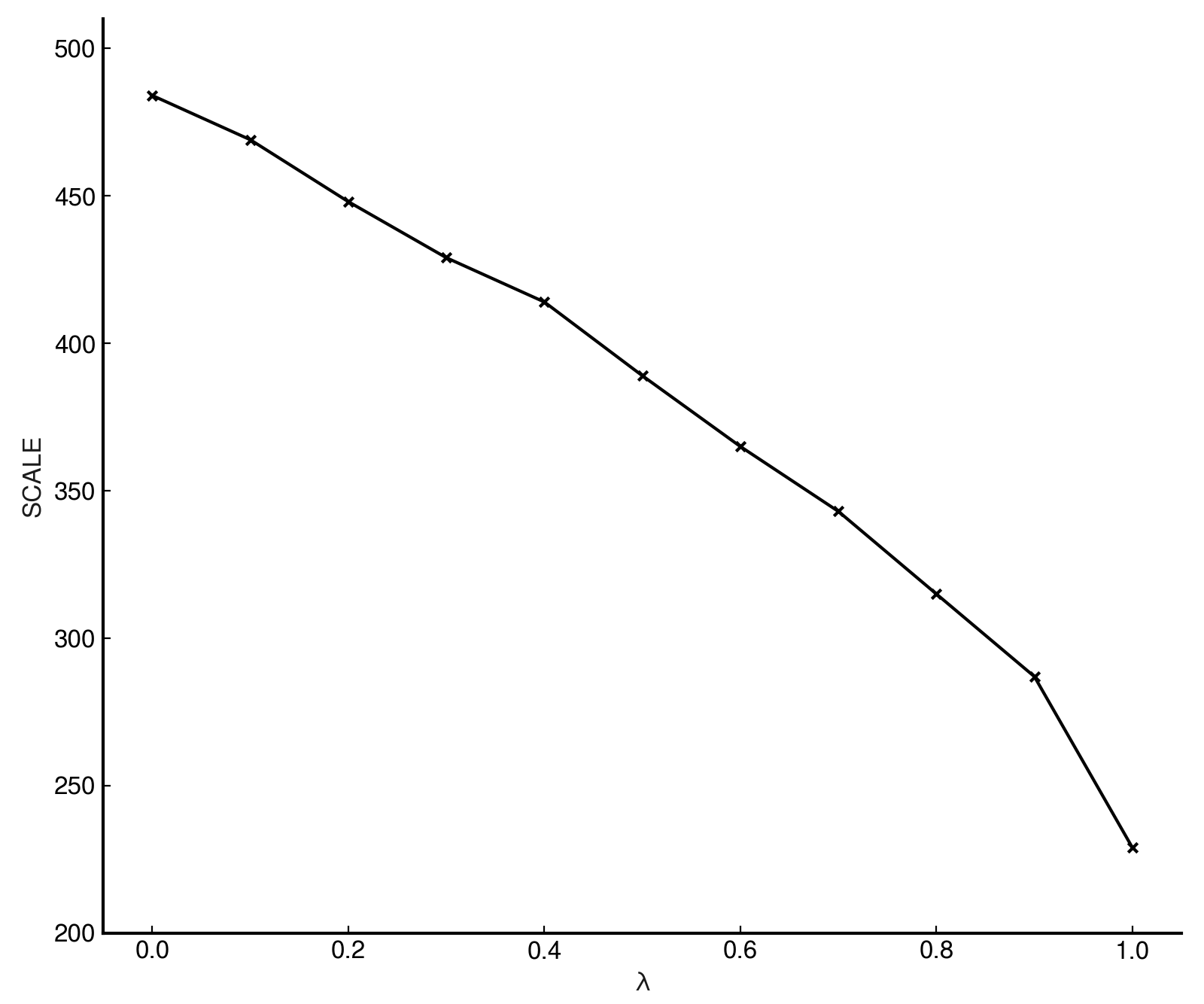

To quantify this effect, 11 smallerEach network was trained with 16 king buckets, 8 output buckets, and a 768 → 256×2 → 16 → 32 → 1 architecture. ↩ test networks were trained with values ranging from 0 to 1 in increments

of 0.1, and the average absolute evaluation of each was measured on a large set of positionslichess-big3-resolved.7z ↩ after training. Before this,

delendaViridithas's master network from 2025-05-18 to 2025-11-27, superseded by eleison. ↩'s average absolute evaluation on the same set of positions was recorded, which was approximately 780.

Here, we show the value that would need to be used to scale the network's output evaluations if we wished

to match the average absolute evaluation of delenda. Call this value the SCALE of the network, defined as:

The results show a monotonic downward trend in the required evaluation scale as increases - and therefore an upward trend in the average absolute evaluation of the networks.

Why do we see this effect?

Consider that when , the network is trained purely to match the engine's evaluations . These evaluations are often decisive even when quite low - an evaluation of +200 centipawns is already totally winning, in most settings.

As such, we have that there are many positions in the training set where a network is being trained to output for positions that are already as good as won. Contrast this with a network, which is being trained to output for these positions - it is fairly easy to see why increasing leads to networks that output larger values on average.

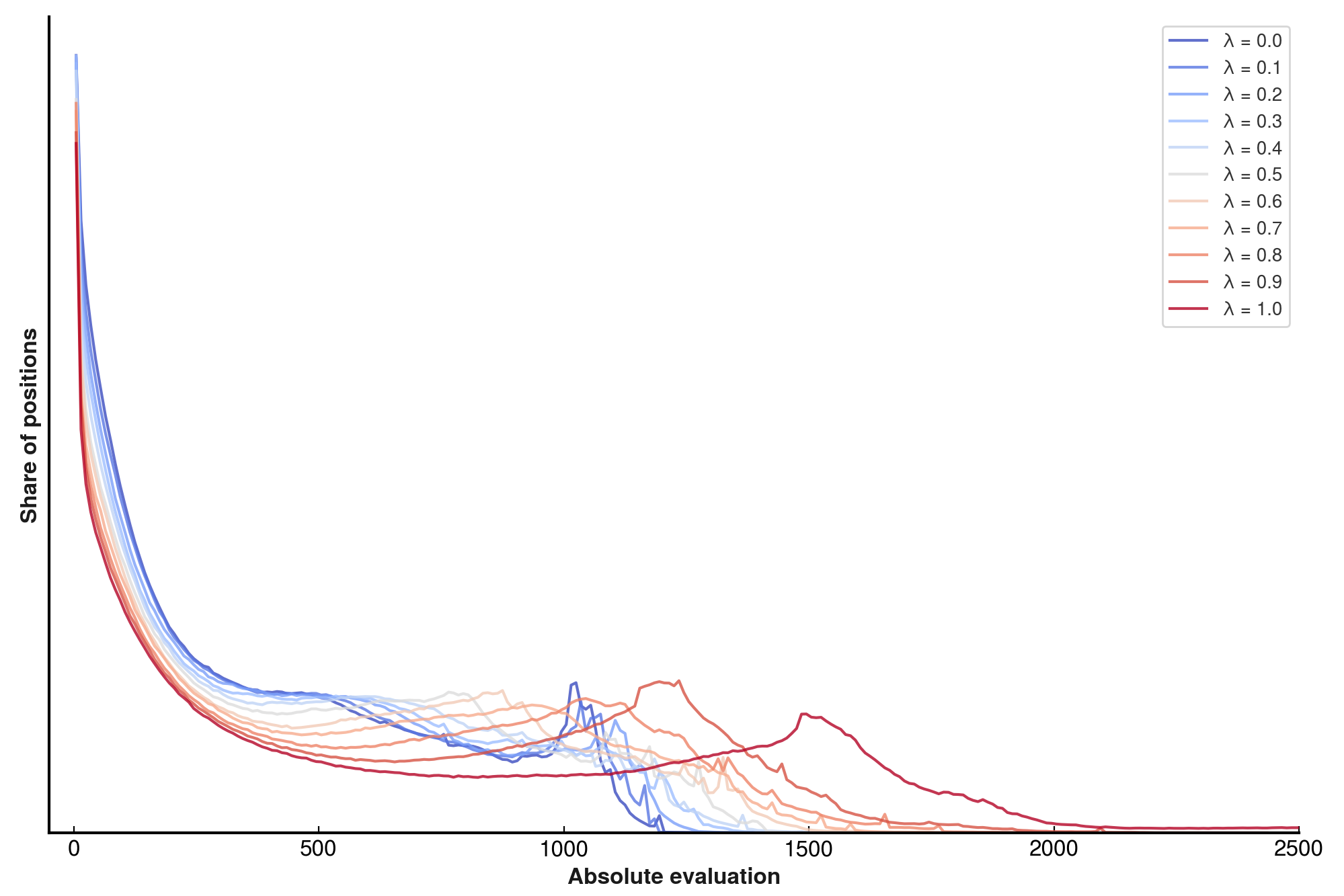

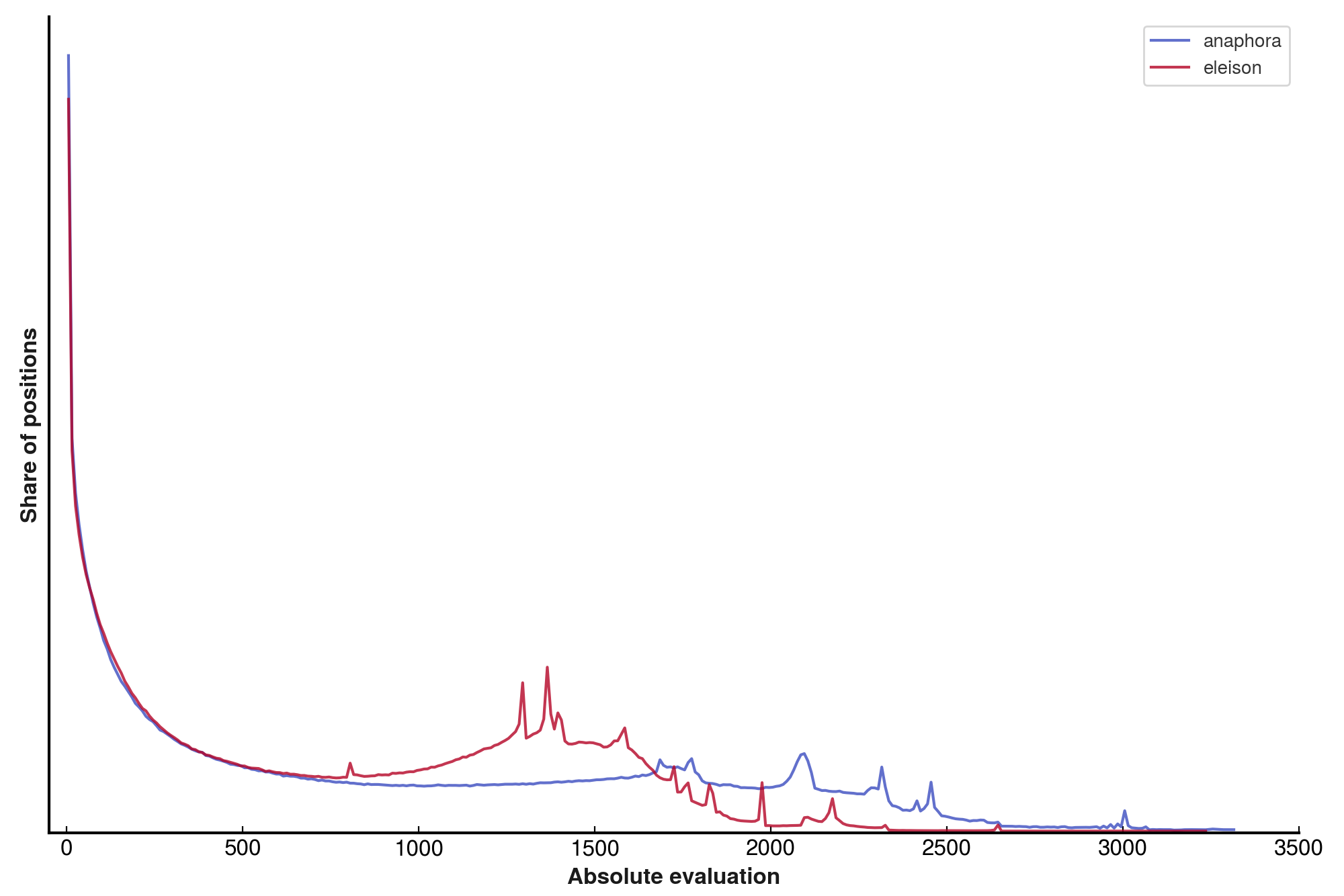

One might want to visualise exactly how evaluation scale varies with , and so the absolute evaluations for these networks were computed and bucketed into 10-unit chunks.

We see that higher stretches the evaluation distribution upwards, and correspondingly decreases the frequency with which lower evaluations are produced. We also see interesting artefacts in the curves - most networks exhibit a “hump” in the high-eval regime, which itself moves rightward with increasing . Interestingly, the intermediate networks through do not obviously exhibit these humps, while extremal networks do!

The importance of rescaling for playing strength

Modern chess engines are highly tuned to work with evaluations on a particular scale. Viridithas, for example, has been

tuned using SPSASimultaneous perturbation stochastic approximation ↩ multiple times - which will have optimised many evaluation-relative heuristic parameters to work well with

the particular evaluation scale exhibited by delenda and her predecessors.

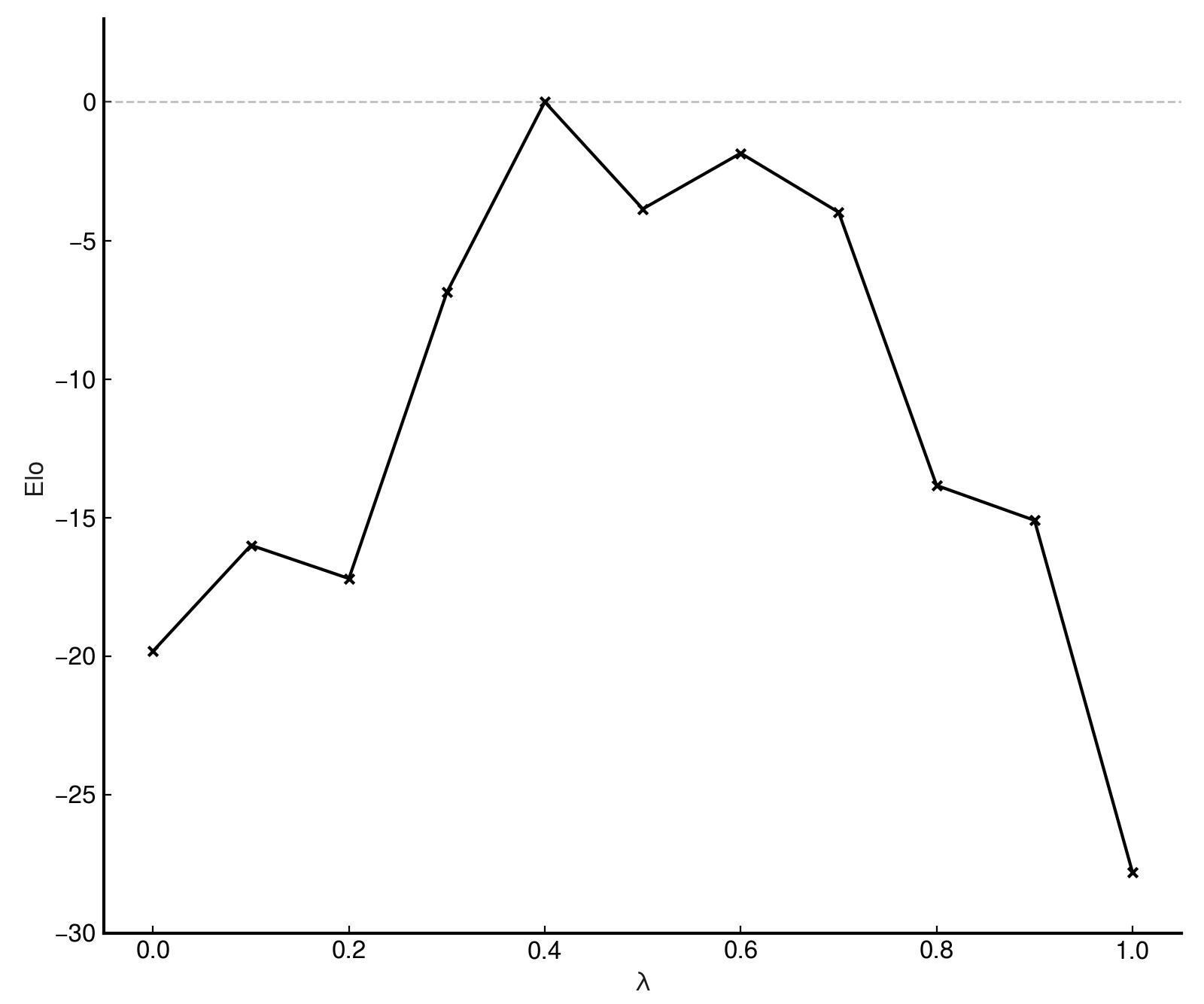

If a network is used without rescaling, and its evaluation scale differs significantly from what the engine expects, then playing strength can be severely degraded. To demonstrate this, the test networks were tested for strength at 25,000 nodes per move, with the test network as a baseline.

As one might expect, performance degrades significantly when evaluation scale diverges from that which the engine is tuned to handle.

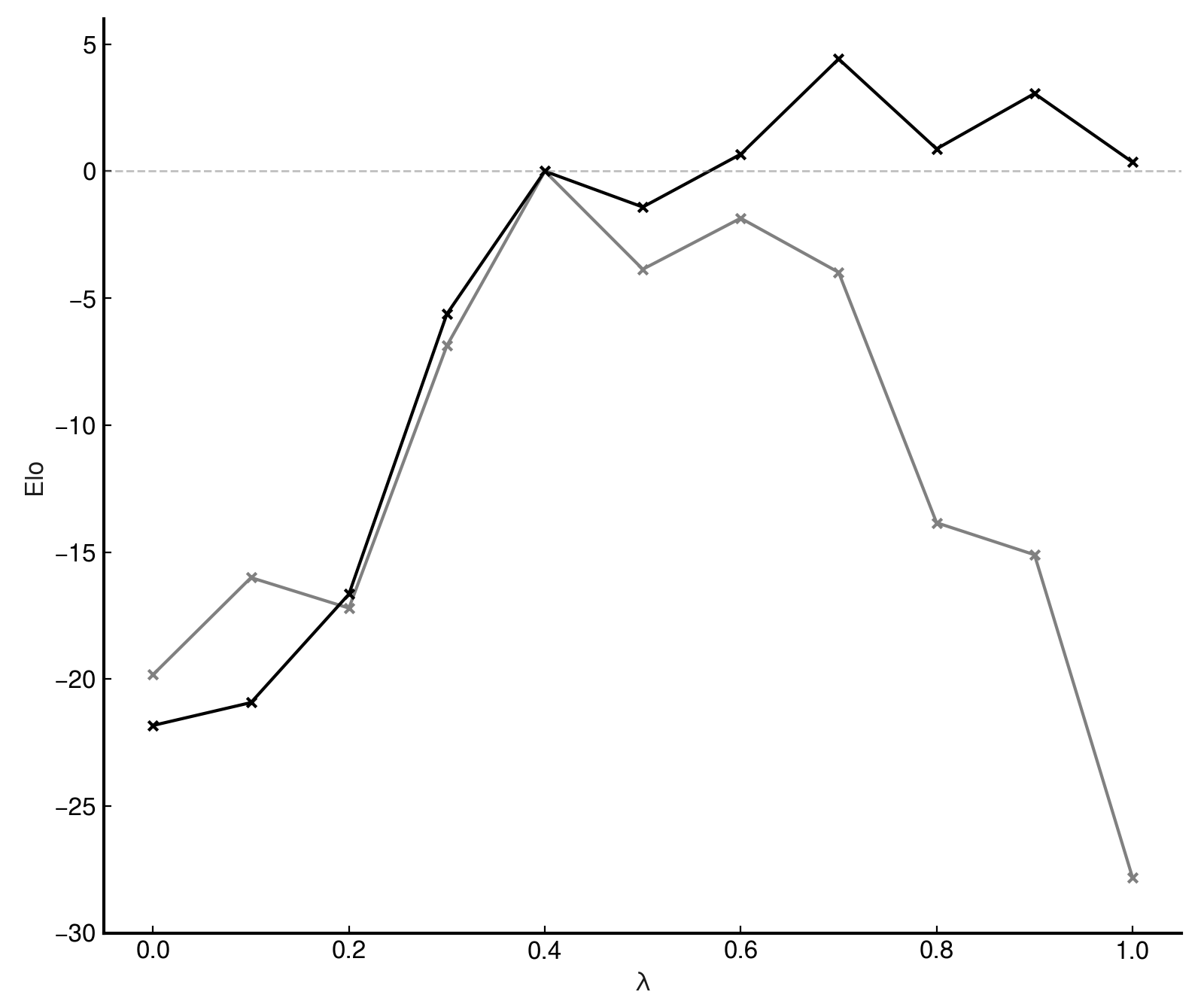

If, instead, the inference-time value for SCALE is changed from 400 to the 229 required to match delenda's average evaluation scale,

the network's performance shoots up to parity with (or even slight superiority to) the network, a

gain of 28 Elo:

Oddly, rescaling does not seem to help the low- networks, even degrading their performance somewhat. Either there is a second factor one must consider when inferencing such networks, or they are genuinely comparatively weak.

Conclusion

The phenomena enumerated here are not obvious a priori from a description of the training procedure, and contributed to a significant quantity

of consternation experienced while attempting to produce a network superior to delenda. When the phenomenon of evaluation scale dependence

on was drawn to my attention, it allowed me to train eleison, a network that uses in the final stages of training,

and which is strongly superior to delendaEleison release ↩.

A final thought: The Viridithas project is currently experimenting with networks that output categorical probabilities for the outcome of the game - that is, a probability distribution over winning, drawing, or losing, instead of a single value indicating the expected value of a position.

These networks are far smoother in the high-evaluation regime.

Food for thought. See you in the next one!